http://bit.ly/TimMcCreadytaxcuts

Tim McCready and James Penn

The Government’s election-year Budget contained $2 billion worth of tax cuts from April next year – on the proviso National gets elected on September 23.

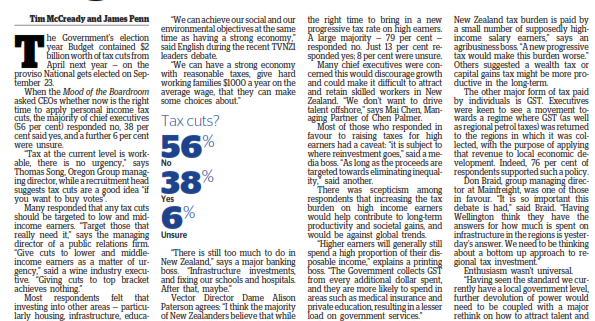

When the Mood of the Boardroom asked CEOs whether now is the right time to cut personal income tax, most (56 per cent) responded no, 38 per cent said yes, and a further 6 per cent were unsure.

“Tax at the current level is workable; there is no urgency,” says Oregon Group managing director Thomas Song. A recruitment head suggests tax cuts are a good idea “if you want to buy votes”.

Many responded that any tax cuts should be targeted to low and mid-income earners. “Target those that really need it,” says the managing director of a public relations firm. “Give cuts to lower and middle-income earners as a matter of urgency,” said a wine industry executive. “Giving cuts to top bracket achieves nothing.”

Most respondents felt that investing into other areas – particularly housing, infrastructure, education, health and climate change – is more important.

But Bill English disputes that you can’t have both.

“We can achieve our social and our environmental objectives at the same time as having a strong economy,” said English during the recent TVNZ leaders debate.

“We can have a strong economy with reasonable taxes, give hard-working families $1000 a year on the average wage, that they can make some choices about.”

“There is still too much to do in New Zealand,” says a major banking boss. “Infrastructure investments, and fixing our schools and hospitals. After that, maybe.”

Vector Director Dame Alison Paterson agrees: “I think the majority of New Zealanders believe that while there are children living below the poverty line, there should be no personal income tax cuts.”

CEOs were asked whether now is the right time to bring in a new progressive tax rate on high earners. A large majority – 79 per cent – responded no. Just 13 per cent responded yes; 8 per cent were unsure.

Many chief executives were concerned this would discourage growth and could make it difficult to attract and retain skilled workers in New Zealand. “We don’t want to drive talent offshore,” says Mai Chen, managing partner of Chen Palmer.

Most of those in favour to raising taxes for high earners had a caveat: “it is subject to where reinvestment goes,” said a media boss. “As long as the proceeds are targeted towards eliminating inequality,” said another.

There was scepticism among respondents that increasing the tax burden on high income earners would help contribute to long-term productivity and societal gains, and would be against global trends.

“Higher earners will generally still spend a high proportion of their disposable income,” explains a printing boss. “The Government collects GST from every additional dollar spent, and they are more likely to spend in areas such as medical insurance and private education, resulting in a lesser load on government services.”

Several CEOs worry that increasing tax on higher earners could lead to an increase in tax avoidance measures. “A huge proportion of the New Zealand tax burden is paid by a small number of supposedly high-income salary earners,” says an agribusiness boss. “A new progressive tax would make this burden worse.” Others suggested a wealth tax or capital gains tax might be more productive in the long-term.

The other major form of tax paid by individuals is GST. Executives were keen to see a movement towards a regime where GST, as well as regional petrol taxes, was returned to the regions in which it was collected, to go towards local economic development. Indeed, 76 per cent of respondents supported such a policy.

Mainfreight group managing director Don Braid is one of those in favour. “It is so important this debate is had,” says Braid. “Having Wellington think they have the answers for how much is spent on infrastructure in the regions is yesterday’s answer. We need to be thinking about a bottom-up approach to regional tax investment.”

Enthusiasm wasn’t universal.

“Having seen the standard we currently have at local government level, further devolution of power would need to be coupled with a major rethink on how to attract talent and experience to move into that space.”

“Daft idea,” said one executive. “Local government would just waste the money.”

Thomas Song’s top three issues

- Productivity: Every factor of input is expensive because of the political insistence on New Zealand labour. If we buy infrastructure, we should buy “quality and speed at cheapest price”. How the supplier delivers shouldn’t be our concern except, of course, slave labour excluded.

- Ignorance of world affairs: Move to educate with diverse sources of teachers from offshore.

- Complacency: The average Kiwi has very little idea about our largest trade partner – China. Most still believe China is still in the Mao era of cheap labour. Again, make knowledge of our trading partners a priority.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!