Infrastructure: Chinese lessons for Kiwis (NZ Herald)

A capital injection will allow China’s ICBC bank to invest further in New Zealand infrastructure projects.

ICBC NZ recently received an additional US$60 million (NZ$88.08m) capital injection from the bank’s head office.

This new funding — approved by ICBC at a time where the global trade and investment environment has been subdued — is a strong signal of the bank’s commitment with New Zealand.

ICBC NZ’s chief executive, Karen Hou, says the additional capital will allow the bank to further invest in local infrastructure projects.

The bank has already invested across a range of industry sectors — including financing support to the banking syndication for Wellington’s Transmission Gully motorway, several key pieces of infrastructure in the Christchurch rebuild, and hopes to do more in the near future.

“Infrastructure continues to be ICBC’s main area of focus,” says Hou.

Selecting infrastructure partners

ICBC is present in 18 countries along the Belt and Road, loaning US$78.6 billion against 288 projects.

Hou says this gives the bank strong capability in global infrastructure, which the bank can leverage for New Zealand projects.

She suggested the Government could establish specific standards for global construction partners, to identify and select the best global companies, including Chinese firms, to bring experience and expertise into the country from across a range of infrastructure classes — bridges, railways, motorways, schools, power and water — along with capital.

“The use of Chinese companies can make the cost lower relative to others due to labour, scale, and the cost of materials,” says Hou.

“At the same time, Chinese technology, management and safety are world-leading.

“We should aim to bring the best from around the world to New Zealand — ICBC would like to assist to introduce and facilitate Chinese top players into the local market.”

The bank is now assisting a delegation of New Zealand Infrastructure companies that plan to visit China next year, in order to learn from China’s most advanced projects, central planning, execution and implementation methods.

“In order to deliver successful projects, it is important to select those companies that have significant global experience on major projects, as well as a good attitude towards

environmental protection,” says Hou.

Making projects more attractive

Though the opportunity for infrastructure investment in New Zealand is significant, Hou notes that the return on projects can be very low and spread over a very long project recovery period, which can make banks cautious about lending.

She says that Chinese companies are interested in the New Zealand market, but they are facing some difficulties here that means they cannot bring their comparative advantage here. These include:

1. Project overruns and delay.

2. It is difficult for some Chinese construction companies to succeed when bidding on tenders, because there is a local experience requirement when you bid.

3. Despite winning a tender, some Chinese companies have to subcontract to local builders, and are unable to take advantage of using their own staff due to a lack of policy support for filling labour shortages that could help rapidly advance infrastructure projects.

Hou says there are opportunities for the Government to help make local infrastructure projects more attractive.

“The Government may choose to partly invest alongside private companies,” she says.

“They could also introduce preferential policies that help support the infrastructure or provide a bottom line for future investment repayments.”

“If the project can be structured well and can balance reasonable returns and a mitigated risk, then it will become very attractive.”

Hou gives two examples of how the Government can help — the BOT public private partnership (PPP) model, and combing smaller infrastructure projects together.

BOT model

The BOT (build, operate, transfer) model is one of the most popular PPP models used in China for delivering major infrastructure projects.

Under the BOT model, the government uses the private sector to design, build and run an infrastructure project. After a period of time the asset is transferred back to the government.

This structure relies on the private sector, but the government supports the private sector to help with regulatory hurdles and ensuring the repayment of the investment makes the project worthwhile.

As an example, when establishing a subway: the cost is designed from the outset, including how to repay the investment. If there is not enough money to repay the investment through the subway alone, the government can help by using other developments associated with the subway — such as the related commercial areas — to go towards the repayment of the project.

This way, getting resources for infrastructure projects is easier because the risk of repayment is lowered.

Combining infrastructure projects

Hou notes that in New Zealand there are many significant infrastructure projects in development ranging in size.

“There is an infrastructure deficit in New Zealand that could be as high as $30 billion,” she says. “Individual projects might range between $200m and $3b, but if smaller projects are combined then it could significantly lower the overall cost.”

She says Chinese construction companies are unlikely to be attracted to New Zealand to undertake one small project.

“Generally, small projects will only attract the small companies, not the high-end companies. In order to attract the biggest and the best to come here, there needs to be a clear pipeline of large projects that will justify bringing people and equipment to this country.”

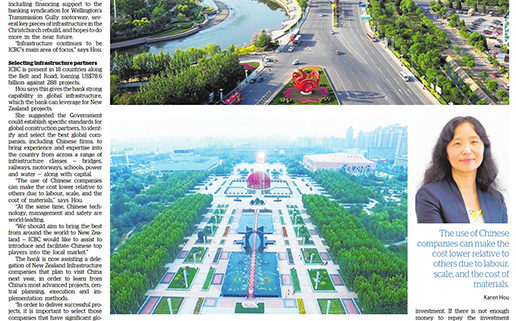

Wuqing: satellite city opportunities

ICBC NZ chief executive Karen Hou is keen for New Zealand to consider inter-city transportation links, such as the line between Beijing and Tianjin that has cut travel time from three hours to around 30 minutes.

“A satellite city provides many infrastructure projects,” she says. “Not only the transportation network between cities, but also development of areas around and along the transportation network.”

Hou says by combining these developments together, the project scale becomes much larger and is more attractive to some of the biggest and best global developers.

One example of this is Wuqing, a satellite city located 70km from Beijing. The Beijing-Tianjin high-speed rail service was introduced in 2008, and includes a one-minute stop in Wuqing.

Wuqing used to be a transport hub, carrying cargo to Beijing along the Grand Canal. But the rise in railway and roading meant until the high-speed rail service was introduced, opportunities in the city were limited.

Since then, Wuqing has been propelled into an important satellite city, attracting more than 8200 projects from Beijing over the past five years, totalling 51.6 billion renminbi, according to the district government.

The city is just 24 minutes from Beijing which makes commuting for work feasible, and it has opened the city up for significant new infrastructure development, offering far more affordable housing options than in Beijing or Tianjin.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!