Infrastructure: Local funding for growth (NZ Herald)

Are restrictions on local government funding mechanisms stifling the ability of our cities to grow at their best?

When running for mayoralty in 2016, Phil Goff made the following commitment on rates:

“Rate rises will be kept low and affordable at an average of 2.5 per cent per annum or less, if current council fiscal projections are correct and the consumer price index stays low.”

The question of how much rates will rise — and the commitment to keep them as low as possible — are cornerstones of any recent Auckland mayoral bid. But there are concerns the current restrictions on local government’s funding mechanisms are stifling the ability of our cities to grow at their best.

Reliance on revenue from rates

In New Zealand, council revenue is largely separated from economic performance.

Local government is the core funder of transport and water services for new development, yet its revenue is derived from property rates — which are a cost allocation method linked to council costs, and not to the success of the economy or land prices.

Conversely, central government is the direct benefactor of growth: receiving increased GST, income tax and corporate tax when the economy grows.

Increased council costs mean an increase in rates, irrespective of economic performance, and any efforts made to charge ratepayers more to deliver additional services — including for those without homes who pay no rates — is consistently met with strong opposition from homeowners.

Councils see little funding benefit from growth, and as a result tend to have a culture of cost minimisation, heavily influencing their decision making at the expense of value creation.

“Importantly, from a local government economic development perspective, property taxes are not the best incentive to encourage councils to invest in infrastructure,” says Local Government Funding Agency chair Craig Stobo.

“If council revenue streams were tied to their performance, successful councils would accrue more revenue, providing more choices for their communities.”

This is not a new concern: a 2015 review into local government funding by Local Government New Zealand (LGNZ) found that the heavy reliance on property taxes to fund local services and infrastructure fails to incentivise councils to invest for growth.

The only other major source of revenue local government currently has in its toolkit is to lobby central government: Shane Jones’ Provincial Growth Fund will see an investment boost in regional New Zealand, and the Housing Infrastructure Fund is aiding high growth councils to advance infrastructure projects that will help increase housing supply.

Yet the patience required for central government to fill the funding gap has seen growth issues turn chronic. Infrastructure New Zealand is concerned that private capital which could have filled the gap has been left searching for opportunities overseas.

Funding and finance inquiry

Local Government Minister Nanaia Mahuta acknowledges the funding challenges faced by local government and the constraints of rate rises, noting they are rising faster than incomes and cannot be the only solution. She says that — if not met — the funding gap will have consequences for local communities and for the entire country.

“Local government is facing increasing costs for things like three waters, roading, housing, and tourism infrastructure as well as adapting to climate change,” she says.

And some of the councils facing the biggest cost increases also have shrinking rating bases.”

Last month the Minister of Finance, Grant Robertson, asked the Productivity Commission to conduct an inquiry into how to fund and finance local government.

The inquiry will investigate:

- Cost and price escalation for services and investment, including whether this is a result of policy and/or regulatory settings

- Current frameworks for capital expenditure decision making, including cost-benefit analysis, incentives and oversight of decision making

- The ability of the current funding and financing model to deliver on community expectations and local authority obligations, now and into the future

- Rates affordability now and into the future

- Options for new funding and financing tools to serve demand for investment and service

- Constitutional and regulatory issues that may underpin new project financing entities with broader funding powers, and

- Whether changes are needed to regulatory arrangements overseeing local authority funding and financing.

Stobo says the terms of reference given to the Commission by Robertson are very good, and the requirement to consult with the sector is a helpful recognition of the expertise the sector can bring to the table.

“Prospectively this could lead to some devolution of tax setting and collection powers to local government, and a cessation of inefficient quota handouts from central government.

“The final results need to improve the incentives for councils to responsibly invest in local growth,” he says.

The New Zealand Initiative’s executive director, Dr Oliver Hartwich, is confident the Productivity Commission will produce good results.

“What is important for the Productivity Commission’s inquiry is to consider the incentives under which local government operates, and the Terms of Reference certainly allow that,” he says. “More specifically, it will allow the commission to consider the OECD’s recommendation to the New Zealand government that councils should participate in tax revenue increases resulting from economic growth.”

The commission’s final report is expected to be presented by November 2019.

Calling for localism

Coinciding with the announcement of an inquiry, LGNZ and The New Zealand Initiative launched their Localism project, calling for a shift in the way public decisions are made in New Zealand by seeking a commitment to localism. LGNZ President and Dunedin Mayor David Cull says it is important the new funding options incentivise growth.

“[The Localism Project] will highlight how the right incentives and funding can build strong local economies and vibrant communities. The urgent need to properly empower councils is reinforced by the fact that decentralised countries tend to have higher levels of prosperity than centralised ones.

“New Zealand is among the most centralised countries in the world.

“We should not expect central government in Wellington to be the best decision-maker for every local problem. Communities often know best what they need.”

The New Zealand Initiative’s Hartwich adds: “After more than a century of centralism, New Zealand needs to go local.

“Councils and communities must be able to make their own decisions about their future.”

A final report and publication of the Localism Proposal is expected in early 2020, and Hartwich notes there will be ample opportunity for the Localism report and the Productivity Commission inquiry to cross-fertilise.

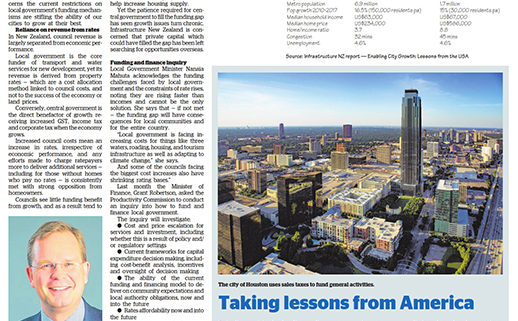

Taking lessons from America

The city of Houston uses sales taxes to fund general activities.

Earlier this year, Infrastructure New Zealand led a delegation of NZ representatives to Portland, Denver, Dallas-Fort Worth, and Houston — four US cities that are growing more affordably than Auckland — to consider how they are doing what they are doing, and what New Zealand can learn from them.

The report, Enabling City Growth: Lessons from the USA, provides detail on the lessons learnt from the visit, including the following on how local authorities are funded:

- US cities have a number of funding mechanisms that are tied to their economic performance. Denver, Dallas, and Houston use sales taxes to fund general activities, and each has levied a 1 per cent sales tax to deliver improved public transport.

- Dallas and Houston have property taxes with a strong link to property value. In each case, the revenue of the city and its component institutions increases with the success of the city in growing the economy and delivering homes.

- Portland, the city with the greatest growth challenges, also has the fewest incentives to grow. There is no sales tax in Oregon, removing this option also for Portland.

- Instead, Oregon relies on comparatively high income and corporate taxes, but has not extended the ability for Portland to levy these direct.

- Property taxes in Portland have been tied to inflation since the early 1990s. Thus, property values have now become detached from property rates and the two are only reviewed when properties are significantly changed or redeveloped.

Infrastructure: Proposals that hold water (NZ Herald)

Suggestions for reform could impact on local councils, reports Tim McCready.

Figures released last month in a Ministry of Health report show one in five New Zealanders are drinking water from water supplies that don’t meet current drinking water standards.

The report shows larger suppliers — including Auckland’s Watercare, Wellington Water, and Dunedin — are meeting compliance standards throughout the year. But many smaller communities are failing to comply, including some of New Zealand’s most iconic tourism destinations: Coromandel, Whangamata, Waitomo Caves, Tekapo and Milford Sound.

In the 2016 outbreak of gastroenteritis in Havelock North, an estimated 5500 of the town’s 14,000 residents became ill with campylobacteriosis and 45 were hospitalised. It was ultimately traced to contamination of drinking water supplied by two bores — with sheep faeces being the likely source of the pathogen.

The Havelock North incident raised serious questions about the safety and security of New Zealand’s drinking water, and sparked a Government Inquiry into the outbreak.

The inquiry made 51 recommendations to improve drinking water safety — including that all water supplies should be treated, and that a dedicated drinking water regulator should be established.

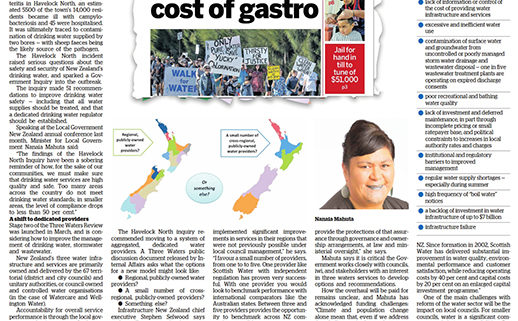

Speaking at the Local Government New Zealand annual conference last month, Minister for Local Government Nanaia Mahuta said:

“The findings of the Havelock North Inquiry have been a sobering reminder of how, for the sake of our communities, we must make sure that drinking water services are high quality and safe. Too many areas across the country do not meet drinking water standards; in smaller areas, the level of compliance drops to less than 50 per cent.”

A shift to dedicated providers

Stage two of the Three Waters Review was launched in March, and is considering how to improve the management of drinking water, stormwater and wastewater.

New Zealand’s three water infrastructure and services are primarily owned and delivered by the 67 territorial (district and city councils) and unitary authorities, or council-owned and controlled water organisations (in the case of Watercare and Wellington Water).

Accountability for overall service performance is through the local government election process. In theory, if the public is unhappy with the performance of their council they will elect new councillors. But in reality, most members of the public do not have the information, capability, or desire to effectively monitor service outcomes. In many cases — including Havelock North — it is not until things go wrong that the public find out the extent of the problem.

The Havelock North inquiry recommended moving to a system of aggregated, dedicated water providers. A Three Waters public discussion document released by Internal Affairs asks what the options for a new model might look like:

- Regional, publicly-owned water providers?

- A small number of cross-regional, publicly-owned providers?

- Something else?

Infrastructure New Zealand chief executive Stephen Selwood says scale really matters in the water business, because as well as enabling economies of scale, it provides the revenue base to maximise skills capability and capacity to govern, fund, oversee and operate water service delivery effectively.

“The value of scale and capability is already being clearly demonstrated by Watercare and Wellington Water who have between successfully implemented significant improvements in services in their regions that were not previously possible under local council management,” he says. “I favour a small number of providers, from one to to five. One provider like Scottish Water with independent regulation has proven very successful. With one provider you would look to benchmark performance with international comparators like the Australian states. Between three and five providers provides the opportunity to benchmark across NZ companies as well.”

Mahuta, who recently returned from a research trip to Scotland and Ireland to consider the models used there, says there are no pre-determined solutions, but a bottom line is continued public ownership of existing three waters infrastructure.

“Any option must ensure continued public ownership of existing infrastructure assets and we must provide the protections of that assurance through governance and ownership arrangements, at law and ministerial oversight,” she says.

Mahuta says it is critical the Government works closely with councils, iwi, and stakeholders with an interest in three waters services to develop options and recommendations.

How the overhaul will be paid for remains unclear, and Mahuta has acknowledged funding challenges: “Climate and population change alone mean that, even if we address the challenges in front of us now, significant funding pressures will continue to arise for decades to come.” Selwood says it should pay for itself, citing Scottish Water as an example:

“This publicly-owned national water service provider delivers drinking and wastewater services to five million people across an urban and rural hinterland comparable to NZ.

Since formation in 2002, Scottish Water has delivered substantial improvement in water quality, environmental performance and customer satisfaction, while reducing operating costs by 40 per cent and capital costs by 20 per cent on an enlarged capital investment programme.”

One of the main challenges with reform of the water sector will be the impact on local councils. For smaller councils, water is a significant component of their responsibilities.

Removing these raises questions about future viability.

Says Selwood: “I think this provides an opportunity to refocus councils from managing utilities and engineering challenges to being more focused on their communities, their people and giving true meaning to local engagement and participation by people in local affairs.”

Sector deficiencies

Successive reports over the past two decades undertaken by a diverse range of agencies and organisations (including the Office of the Auditor General, Water New Zealand, Engineering New Zealand, Infrastructure New Zealand, the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment and the Local Government Infrastructure Efficiency Expert Advisory Group) have pointed to serious deficiencies across the sector. Between them, these expert bodies have compiled a compelling case for change.

- Major challenges include:

- lack of information about the state of infrastructure assets — especially in small rural councils

- lack of information or control of the cost of providing water infrastructure and services

- excessive and inefficient water use

- contamination of surface water and groundwater from uncontrolled or poorly managed storm water drainage and wastewater disposal — one in five wastewater treatment plants are operating on expired discharge consents

- poor recreational and bathing water quality

- lack of investment and deferred maintenance, in part through incomplete pricing or small ratepayer base, and political constraints to increases in local authority rates and charges

- institutional and regulatory barriers to improved management

- regular water supply shortages — especially during summer

- high frequency of “boil water” notices

- a backlog of investment in water infrastructure of up to $7 billion

- infrastructure failure.

Infrastructure: Is New Zealand prepared for artificial intelligence on its roads and infrastructure? (NZ Herald)

The Herald spoke to industry leaders to understand the AI opportunities for New Zealand, and what it could mean for the future of our roads and infrastructure.

How prepared is NZ for artificial intelligence on its roads and other infrastructure?

Hikmet: Prepared? It’s already out there and has been for decades! Adaptive braking, parallel parking assistance, lane-keeping systems, driver fatigue sensors, adaptive traffic control systems. There is so much artificial intelligence already around you and not just on the roads.

Ensor: It is hard to prepare when there is so much uncertainty around what changes artificial intelligence will create. We need to wait before making bets on which emerging technologies will dominate.

Duggan: KPMG’s 2018 Autonomous Vehicles Readiness Index (AVRI) made some interesting headway in this regard, examining a cross-section of 20 countries in terms of their progress and capacity for adopting autonomous vehicle technology — New Zealand was deemed to be in the middle of the pack, in ninth place. The Index evaluated each country according to four pillars integral to a country’s capacity to adopt and integrate autonomous vehicles: Policy & Legislation, Technology & Innovation, Infrastructure and Consumer Acceptance. Advances in vehicle intelligence are happening at a far greater rate than advances in infrastructure; this is where our biggest current challenges lie.

There have been some recent scares involving autonomous vehicles – notably the Uber accident in Arizona that killed a pedestrian. Will momentum slow because of these concerns?

Hikmet: Autonomous vehicle developers and government need to work together to ensure that what’s happening is safe. If we see more of these deaths, public opinion can turn against autonomous vehicles – which would be a real shame. That isn’t to say autonomous vehicles are completely safe, but our current roads are far from it and we should be doing everything we can to reduce deaths. Autonomous vehicles are one way this number can be reduced.

Ensor: That was a tragic example of how today’s autonomous vehicles need to keep learning. It’s important that the hype around autonomous vehicles loses some momentum and we understand better what their capabilities will be and their limitations.

Edwards: The accidents involving autonomous vehicles have dampened enthusiasm among the public but people seem to have forgotten that many accidents occur when there is a human at the wheel. Throughout history there are examples where new technologies have ended in tragic circumstances — like the Hindenburg airship and the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion. These incidents temporarily set back developments in their field, but long term, the lessons learned enabled the technologies to become safer and obstacles were overcome.

Reid: We still think of autonomous vehicles as something novel and new — however in the US, Alphabet-owned Waymo recently announced their test fleet has driven seven million miles. As with all exponential technologies people will be surprised at how quickly autonomous vehicles become part of our daily lives — and will quickly be demonstrated being as safe as a human driver — then very quickly far exceed the safety performance of human drivers.

What challenges does New Zealand’s roading (and other) infrastructure bring for the introduction of autonomous vehicles?

Hikmet: Many of the autonomous vehicles being built for the road are being trained and designed for driving on the right-hand side — it’s not a completely trivial task to convert them and will require intentional effort from developers to change them over. We also haven’t decided on a communication range for vehicular communication — we can either go with the Europe/US standard or the Japanese one.

Ensor: I hope the major manufacturers will train their autonomous vehicles to drive on the left. The most important thing is to make changes to help autonomous vehicles avoid making mistakes in challenging areas, particularly around roadworks and schools.

Edwards: People forget there are already many autonomous vehicles at work in airports, warehouses, ports and mining to name a few and these are playing a significant part in reducing health and safety risk. These are largely in confined areas rather than on the open road so the infrastructure is planned for this. It becomes exponentially more difficult on the open road system because the increase in variables is so dramatic.

Duggan: The consistency and quality of road markings and signage (or lack of) presents a very real challenge for today’s semi-autonomous vehicles, of which there are an increasing number of models on our roads. GPS accuracy and the next generation of wireless connectivity (5G) will also become increasingly critical considerations. In simple terms, AI is about the collection, processing and evaluation of data from multiple sources to ensure the highest quality of decision-making … autonomous vehicles will be fitted with more sensors than ever before, and infrastructure has a vital role to play in terms of data accuracy and processing speeds. Developments in autonomy and electrification have traditionally taken place in parallel, but their paths have now converged to the extent it’s now widely accepted there won’t be a fully autonomous vehicle that isn’t also electric, so charging infrastructure will have a key role to play by default.

What opportunities would the introduction of autonomous vehicles bring to New Zealand? How could their introduction influence future infrastructure?

Hikmet: The introduction of autonomous vehicles (not just autonomous cars) will allow many people to regain a sense of freedom and independence that they may have lost or never had. Autonomous vehicles also mean you won’t need to invest in close parking, you can instead turn that space into something more productive. I’m certain that the first urban generation who won’t need a driver’s licence has already been born in New Zealand.

Ensor: Autonomous vehicles give greater travel opportunities for people who currently rely on others to drive them or who use public transport. Demand for infrastructure may increase if this makes it easier to travel in a car by yourself.

Reid: The AI Forum’s recent report Artificial Intelligence – Shaping a Future New Zealand identifies a long list of AI applications which could benefit New Zealand across many sectors: agriculture, finance, tourism as well as the growing tech export sector. In the context of infrastructure, here are just a few ideas:

- Health & Safety: using cameras, automated sensors to anticipate dangerous situations and respond. Also, automated robotics have the potential to do all the dirty, dangerous jobs involved in infrastructure — while being intelligently aware of maintaining human safety around them.

- Process automation: throughout the whole process of contracts, design, earthmoving, construction, cable laying. Wherever there is a large amount of data, machine learning enables businesses to identify patterns, make better predictions and optimise processes.

- Simplifying contracts: currently natural language AI is being used to better understand complex legal contracts and identify key clauses to focus on. Given the sums of money involved in infrastructure projects, this is a key tool for both parties to a contract to help ensure that hidden risks are reduced.

- Monitoring project progress: using cameras and machine vision to automatically measure project progress. Christchurch GeoAI company Orbica are doing amazing work in this space using satellite imagery to identify how far building construction has progressed.

Personally, I reckon there’s an opportunity for autonomous “swarm bots” in the infrastructure sector — for example a swarm of little earth moving robots controlled by a “hive mind”could deliver all sorts of potential improvements for output, speed, precision, energy efficiency and safety. You heard it here first.

Duggan: Courtesy of features such as intelligent cruise control, steering support with ‘lane keeping’ technology and Autonomous Emergency Braking, the ‘semi-autonomous’ vehicles on our roads today have already begun to have a positive impact by reducing the frequency and severity of accidents. It’s no coincidence that autonomous vehicles have become increasingly topical at a time when in major cities around the world populations are outgrowing infrastructure, air quality is deteriorating, traffic accidents have become a global health issue and commute times continue to increase. Whether in London, Shanghai, Sydney or Auckland, fully autonomous vehicles are geared towards improving the productivity, sustainability, efficiency and safety of our daily commute.

Downstream, there’s no question that the advent of fully autonomous vehicles will influence social behaviour in relation to mobility, which will in turn influence the layout of our cities.

Is there an opportunity for New Zealand to propel itself to the forefront in this area?

Hikmet: New Zealand, particularly Christchurch, is pretty close to the forefront here. Christchurch International Airport’s autonomous vehicle trial is just about to wrap up, and they have ordered the first Ohmio LIFT which will be deployed there — making it one of the first airport autonomous vehicle deployments in the world. I know that some of the largest airports in the world are keenly observing and asking Christchurch Airport about their experience with autonomous vehicles. NZTA are also working with Christchurch City Council to operate parts of the Red Zone into an autonomous vehicle testing ground.

Ensor: With the amount of money being invested in research by major global companies, New Zealand needs to look our skills in “making things happen”. We could focus on removing specific technological barriers that vehicles will face driving in countries like New Zealand.

Edwards: I am concerned that the wheels of decision making turn too slowly here. NZ has some great minds working on AI development, robotics and so on, but in the technology world, you need an entrepreneurial mindset where you are allowed to experiment and sometimes fail in the interests of learning. In this country we tend to debate policy and regulation over months and sometimes years, by which time key opportunities can be lost. When it comes to infrastructure, our low tax base means that financial commitments to major infrastructure projects will be scrutinised and held up by competing priorities. New Zealanders (and the media) can be very intolerant of false starts and prototype failures, which is not conducive to experimentation and will hold this country back, particularly in the infrastructure space.

Reid: As a country our non-tech sector businesses need to think ahead more beyond next quarter’s profit numbers and start investing in long term data and technology-driven innovation. Our productivity remains pretty static and there are increasing signs that we are falling behind other OECD countries in terms of our economic competitiveness. While technology is not the only factor we will only reap the rewards of these new technologies if we invest in R&D and develop a deeper innovation capability throughout our business culture. Otherwise we will just be downstream consumers and price-takers from overseas tech firms.

Duggan: While New Zealand’s legal framework is relatively “autonomous vehicle friendly” and Kiwis are known for being early adopters of technology, the size of our market, our remote location relative to vehicle development and manufacturing facilities, our topography and low population density, and our current infrastructure are all barriers which will prevent New Zealand positioning itself at the forefront of autonomous vehicle testing and implementation. It’s critically important that we keep up in terms of investment in infrastructure — which will have far broader benefits than for autonomous vehicles alone — and there’s no question that the vehicle technology available to us is advancing at a greater rate than ever before, but I’m not convinced there’s a need for New Zealand to adopt a leadership position in this regard.

What other areas of artificial intelligence do you think will influence New Zealand’s infrastructure development?

Ensor: We need to look at how artificial intelligence can speed up the way we design, consent and construct infrastructure projects. Embedding artificial intelligence into these processes could shorten the time required to deliver large infrastructure projects by months or even years.

Hikmet: Machine learning and computer vision will help with analytics: counting pedestrians or telling you how busy a road is, how many vehicles are on it, and how fast they’re going. You can then use that generated data for analytics and predictive modelling. If urban planners and transport operators are more aware of what impact different decisions (be it infrastructure or policy) will have, they will make better choices to bring about the change that’s really needed for their specific communities.

Infrastructure: Chinese lessons for Kiwis (NZ Herald)

A capital injection will allow China’s ICBC bank to invest further in New Zealand infrastructure projects.

ICBC NZ recently received an additional US$60 million (NZ$88.08m) capital injection from the bank’s head office.

This new funding — approved by ICBC at a time where the global trade and investment environment has been subdued — is a strong signal of the bank’s commitment with New Zealand.

ICBC NZ’s chief executive, Karen Hou, says the additional capital will allow the bank to further invest in local infrastructure projects.

The bank has already invested across a range of industry sectors — including financing support to the banking syndication for Wellington’s Transmission Gully motorway, several key pieces of infrastructure in the Christchurch rebuild, and hopes to do more in the near future.

“Infrastructure continues to be ICBC’s main area of focus,” says Hou.

Selecting infrastructure partners

ICBC is present in 18 countries along the Belt and Road, loaning US$78.6 billion against 288 projects.

Hou says this gives the bank strong capability in global infrastructure, which the bank can leverage for New Zealand projects.

She suggested the Government could establish specific standards for global construction partners, to identify and select the best global companies, including Chinese firms, to bring experience and expertise into the country from across a range of infrastructure classes — bridges, railways, motorways, schools, power and water — along with capital.

“The use of Chinese companies can make the cost lower relative to others due to labour, scale, and the cost of materials,” says Hou.

“At the same time, Chinese technology, management and safety are world-leading.

“We should aim to bring the best from around the world to New Zealand — ICBC would like to assist to introduce and facilitate Chinese top players into the local market.”

The bank is now assisting a delegation of New Zealand Infrastructure companies that plan to visit China next year, in order to learn from China’s most advanced projects, central planning, execution and implementation methods.

“In order to deliver successful projects, it is important to select those companies that have significant global experience on major projects, as well as a good attitude towards

environmental protection,” says Hou.

Making projects more attractive

Though the opportunity for infrastructure investment in New Zealand is significant, Hou notes that the return on projects can be very low and spread over a very long project recovery period, which can make banks cautious about lending.

She says that Chinese companies are interested in the New Zealand market, but they are facing some difficulties here that means they cannot bring their comparative advantage here. These include:

1. Project overruns and delay.

2. It is difficult for some Chinese construction companies to succeed when bidding on tenders, because there is a local experience requirement when you bid.

3. Despite winning a tender, some Chinese companies have to subcontract to local builders, and are unable to take advantage of using their own staff due to a lack of policy support for filling labour shortages that could help rapidly advance infrastructure projects.

Hou says there are opportunities for the Government to help make local infrastructure projects more attractive.

“The Government may choose to partly invest alongside private companies,” she says.

“They could also introduce preferential policies that help support the infrastructure or provide a bottom line for future investment repayments.”

“If the project can be structured well and can balance reasonable returns and a mitigated risk, then it will become very attractive.”

Hou gives two examples of how the Government can help — the BOT public private partnership (PPP) model, and combing smaller infrastructure projects together.

BOT model

The BOT (build, operate, transfer) model is one of the most popular PPP models used in China for delivering major infrastructure projects.

Under the BOT model, the government uses the private sector to design, build and run an infrastructure project. After a period of time the asset is transferred back to the government.

This structure relies on the private sector, but the government supports the private sector to help with regulatory hurdles and ensuring the repayment of the investment makes the project worthwhile.

As an example, when establishing a subway: the cost is designed from the outset, including how to repay the investment. If there is not enough money to repay the investment through the subway alone, the government can help by using other developments associated with the subway — such as the related commercial areas — to go towards the repayment of the project.

This way, getting resources for infrastructure projects is easier because the risk of repayment is lowered.

Combining infrastructure projects

Hou notes that in New Zealand there are many significant infrastructure projects in development ranging in size.

“There is an infrastructure deficit in New Zealand that could be as high as $30 billion,” she says. “Individual projects might range between $200m and $3b, but if smaller projects are combined then it could significantly lower the overall cost.”

She says Chinese construction companies are unlikely to be attracted to New Zealand to undertake one small project.

“Generally, small projects will only attract the small companies, not the high-end companies. In order to attract the biggest and the best to come here, there needs to be a clear pipeline of large projects that will justify bringing people and equipment to this country.”

Wuqing: satellite city opportunities

ICBC NZ chief executive Karen Hou is keen for New Zealand to consider inter-city transportation links, such as the line between Beijing and Tianjin that has cut travel time from three hours to around 30 minutes.

“A satellite city provides many infrastructure projects,” she says. “Not only the transportation network between cities, but also development of areas around and along the transportation network.”

Hou says by combining these developments together, the project scale becomes much larger and is more attractive to some of the biggest and best global developers.

One example of this is Wuqing, a satellite city located 70km from Beijing. The Beijing-Tianjin high-speed rail service was introduced in 2008, and includes a one-minute stop in Wuqing.

Wuqing used to be a transport hub, carrying cargo to Beijing along the Grand Canal. But the rise in railway and roading meant until the high-speed rail service was introduced, opportunities in the city were limited.

Since then, Wuqing has been propelled into an important satellite city, attracting more than 8200 projects from Beijing over the past five years, totalling 51.6 billion renminbi, according to the district government.

The city is just 24 minutes from Beijing which makes commuting for work feasible, and it has opened the city up for significant new infrastructure development, offering far more affordable housing options than in Beijing or Tianjin.